Mapping Critical Communication Infrastructure on the Seafloor and in Space

Since 2022, there have been at least ten incidents involving underwater cables in the Baltic Sea. Between November and January, additional cables were damaged, disrupting telecommunications links across several Baltic countries. Ships have been detained that may have accidentally cut cables while dragging anchors. Still, the pattern of these events, combined with rising tensions, continues to raise concerns about sabotage (McNamara, 2024).

Space infrastructures are also facing growing threats. Satellites capable of physically grappling others have been launched and technologies that can hijack or disable enemy systems by imitating legitimate control signals have been developed (Muncaster, 2025). Additionally, Ukraine's use of Starlink has been disrupted.China has launched satellites capable of physically grappling others and is developing technologies that can hijack or disable enemy systems by imitating legitimate control signals (Muncaster, 2025). Additionally, Russia has disrupted Ukraine’s use of Starlink, denying a critical component of Ukraine’s tactical operations (Mozur & Satariano, 2024). These pose risks to space-based communications, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and weapons systems.

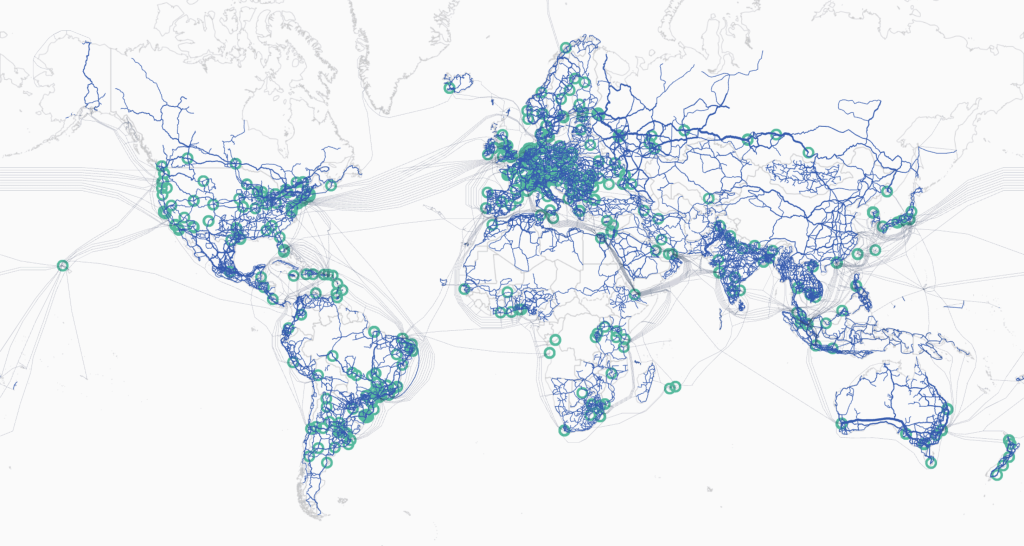

While this post centers on undersea and space-based data transmission infrastructure, it's important to recognize that terrestrial fiber, undersea cables, and space communications systems are deeply interconnected. Although they are often treated as separate entities, these domains are highly interdependent. A significant disruption in one can cascade across the others, amplifying the overall impact. Generally, we have good mapping of the terrestrial data infrastructure. However, there is a critical need to map communications infrastructure in the undersea and space domains.

Interconnected Infrastructure

While many assume undersea and space-based communications infrastructures operate independently, they work together to form an efficient and resilient intercontinental network. Submarine cables and satellites both play essential roles in global communications. Fiber optic submarine cables can carry up to hundreds of terabits per second, making them the primary conduit for global internet traffic. In contrast, satellites, especially geostationary ones, offer far lower data capacity, typically in gigabits per second, though Low Earth Orbit (LEO) constellations like Starlink are narrowing this gap. Latency is another critical factor. Submarine cables offer low latency, while geostationary satellites experience higher latency due to their altitude. LEO satellites offer improved latency, often comparable to terrestrial systems but still generally slower than direct cable routes. Despite these differences, both technologies complement rather than replace each other. Today, undersea cables carry 99 percent of intercontinental data and link ground stations that control space communications assets (McNamara, 2024). Together, these systems provide redundancy, flexibility, and continuous connectivity.

Critical Infrastructure

Critical infrastructure supports essential systems that keep society and the global economy running, including telecommunications, energy, transportation, and defense. In this case, we are focusing specifically on communications infrastructure. Whether accidental or intentional, disruptions to these systems can threaten national security, economic stability, and public safety. The ocean floor and outer space are two domains that demand urgent attention. Much infrastructure in these domains lies beyond national borders and outside sovereign control, making it more vulnerable to exploitation and attack. These networks are vast, rapidly expanding, increasingly critical, and exposed to hostile actors. To protect them, we must know precisely where their components are located and how the components interact over time. Accurate and continuous mapping is a national security imperative.

Mapping Infrastructure

In simple terms, infrastructure mapping documents the connectivity of different networks. Mapping allows us to optimize these systems and prevent and mitigate damage. Mapping enables monitoring, better infrastructure management, damage prevention, and faster response to incidents.

Several organizations are involved in mapping undersea cables. Commercially, firms like TeleGeography maintain global submarine cable maps. On the standards and geospatial side, the International Cable Protection Committee (ICPC), International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), and Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) collaborate to provide technical frameworks for geospatial mapping and cable protection (Monaco, 2025). NATO and national navies are increasingly involved, particularly through centers like NATO MARCOM and national seabed mapping efforts (Monaghan et al., 2023).

The legal framework for submarine cables stems from treaties such as the 1884 Convention and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), but gaps remain. Ownership typically falls to consortia, private corporations, or public private partnerships. Jurisdiction becomes murky once cables cross into international waters, complicating enforcement and protection. In some cases, it is unclear whether national laws apply along certain cable routes, especially those beyond a country’s exclusive economic zone (NBR, n.d.).

Cable owners, whether governments, telecom firms, or content providers, often withhold precise undersea cable locations to reduce vulnerability to sabotage or competitive disadvantages. This reluctance is especially strong in contested or geopolitically sensitive waters. Nations have even been hesitant to release detailed locations to allies due to legal ambiguities and commercial secrecy (Monaghan et al., 2023; NBR, n.d.). The absence of standardized legal frameworks across jurisdictions exacerbates these concerns.

Barriers to Mapping Undersea Infrastructure

While terrestrial infrastructure mapping has matured due to accessibility and established surveying practices, the seafloor and space mapping remains inadequate. Detailed mapping of undersea cables involves expensive bathymetric surveys and results in often proprietary data. In contrast, space mapping depends on ground-based and orbital radar to track objects in three dimensions that are moving at 7.8 kilometers per second (Hall, n.d.). These differences create differences in accuracy, transparency, and update frequency. However, one commonality is the reliance on an Earth-centered coordinate system to integrate spatial data across domains. This shared geospatial framework offers a potential bridge for more unified mapping, analysis, and protection strategies.

Terrestrial and Undersea Data Transmission Infrastructure. Source: https://techterms.com/img/xl/backbone_365.png

Evolution of Mapping Space

Since undersea telecommunications cables form the backbone of global connectivity, a single break can disrupt financial markets, cloud services, and military command and control systems. Adversaries understand this well. Targeted attacks or covert sabotage could cripple digital communications. Natural hazards such as earthquakes, undersea landslides, and anchor strikes pose additional risks. Mapping the seafloor allows for the identification, monitoring, and protection of these vital systems, supporting both preventive maintenance and rapid response. It also informs redundancy planning and route optimization to reduce single points of failure. Space infrastructure is equally critical. Satellites enable global communications, secure military networks, early warning systems, intelligence surveillance, and precision navigation. RAND estimates that seven to twenty trillion dollars in annual economic activity depends on space-based systems (Antoun et al., 2024). Yet space is increasingly contested. Satellite networks face cyberattacks, kinetic threats like anti-satellite missiles, and hazards from orbital debris. The 2022 cyberattack on commercial satellites before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine illustrated how space assets can become frontline targets. As the number of satellites, particularly LEO constellations, grows, precise mapping is essential for tracking objects, preventing collisions, and protecting high value assets.

Space governance faces significant challenges due to an outdated legal framework, rapid technological change, and expanding commercial activity. Core agreements such as the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 offer general guidelines but lack effective enforcement. As commercial activity grows, questions around property rights and jurisdiction become more complex. The development of military technologies, including anti-satellite weapons, adds further difficulty to an already strained system (Bacastow, n.d.).

A wide range of objects in orbit around Earth need to be mapped, including operational satellites, defunct spacecraft, rocket bodies, and fragments of space debris, especially those in LEO and GEO, where most critical infrastructure is concentrated. Mapping of these objects is conducted by a mix of government agencies and commercial companies. The U.S. military, through the Space Surveillance Network (SSN), tracks around 47,000 objects using ground-based radars and optical telescopes, though this Cold War era infrastructure is struggling to keep pace with modern threats and satellite proliferation (U.S. Air Force, 2025). Commercial companies like LeoLabs and ExoAnalytic Solutions supplement these efforts by deploying phased array radars and leveraging AI to detect and predict satellite and debris trajectories (McGlynn, 2018). Mapping plays a foundational role in securing space-based infrastructure by generating precise and up to date spatial information, enabling analysts to detect potential collisions, track adversarial activities, and monitor the growing cloud of space debris. AI enhanced mapping systems are also emerging as critical tools to automate detection and response processes, allowing for faster and more accurate threat assessments (RAND Corporation, 2024).

Protecting the Interconnected Super Infrastructure

Given the growing complexity and interdependence of global communications infrastructure, mapping is foundational to protecting the systems that power modern society. This article underscores the essential role that both undersea cables and space-based communications infrastructure play in supporting global connectivity, and financial and national security. These systems form the backbone of international data transfer yet face increasing risks from accidental damage and deliberate attacks by state actors. Despite their strategic importance, protection of these infrastructures remains inadequate. A key component of strengthening their resilience is comprehensive mapping that enables situational awareness, threat detection, and effective emergency response. We need enhanced cooperation among allies, including intelligence sharing, national risk assessments, public private coordination, and international legal reforms to ensure that both undersea and space-based systems are secured against evolving threats.

Bibliography

Antoun, J., Bega, A., Brady, K., Chandler, R., Cherney, S., Frelinger, D. R., & Szayna, T. S. (2024). How to analyze gray zone operations: Methods, tools, and concepts (RR-A2875-1). RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2875-1.html

Bacastow, T. S. (n.d.). GEOINT and Space Situational Awareness (SSA): Part 2 – Do the cultures align? DGI 2025 Blog. Retrieved June 25, 2025, from https://dgi.wbresearch.com/blog/geoint-and-space-situational-awareness-do-the-cultures-align

ENISA. (2025a, March 26). ENISA Probes Space Threat Landscape in New Report. Infosecurity Magazine. https://www.infosecurity-magazine.com/news/enisa-probes-space-threat/:contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}

ENISA. (2025b, March 27). ENISA space threat landscape report highlights cybersecurity gaps in commercial satellites, urges enhanced defense. Industrial Cyber. https://industrialcyber.co/vulnerabilities/enisa-space-threat-landscape-report/:contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}

McGlynn, D. (2018, June 2). Space mapping. Berkeley Engineer. https://engineering.berkeley.edu/news/2018/06/space-mapping/

Gordon, L. W., & Jones, K. L. (2022, February 1). Global communications infrastructure: Undersea and beyond. The Aerospace Corporation, Center for Space Policy and Strategy. https://aerospace.org

Hall, S. (n.d.). Low Earth orbit: Everything you need to know. Space.com. Retrieved July 2, 2025, from https://www.space.com/low-earth-orbit

Livadariu, I., Elmokashfi, A., & Smaragdakis, G. (2024). Tracking submarine cables in the wild. Computer Networks, 242, 110234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110234

MAPSIT Steering Committee. (2025, March). The Mapping and Planetary Spatial Infrastructure Team (MAPSIT): Terms of Reference. NASA Planetary Science Division. https://www.lpi.usra.edu/mapsit/

McNamara, E. M. (2024, August 28). Reinforcing resilience: NATO’s role in enhanced security for critical undersea infrastructure. NATO Review. https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2024/08/28/reinforcing-resilience-natos-role-in-enhanced-security-for-critical-undersea-infrastructure/index.html

Monaco, C. (2025, May 20). How geospatial standards secure undersea cables. Open Geospatial Consortium. https://www.ogc.org/blog-article/the-vital-role-of-undersea-cable-infrastructure

Morris, C. (2012). Operation Ivy Bells: Lessons learned from an "intelligence success". Journal of the Australian Institute of Professional Intelligence Officers, 20(3), 17–29. Mozur,

P., & Satariano, A. (2024, May 24). Russia is increasingly blocking Ukraine’s Starlink service. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/24/technology/ukraine-russia-starlink.html

Muncaster, P. (2025). China Developing Anti-Satellite Weapons. Infosecurity Magazine. https://www.infosecurity-magazine.com/news/china-developing-antisatellite/:contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}

Monaghan, S., Svendsen, O., Darrah, M., & Arnold, E. (2023, December). NATO’s role in protecting critical undersea infrastructure. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/natos-role-protecting-critical-undersea-infrastructure

National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). (n.d.). Factsheet: Submarine cables – Maritime Awareness Project. https://map.nbr.org/2018/07/submarine-cables

Radebaugh, J., & Hagerty, J. (2019, September 24). MAPSIT roadmap update. Planetary Science Advisory Committee. https://www.lpi.usra.edu/mapsit/

RAND Corporation. (2024). Artificial intelligence for space domain awareness: Opportunities and challenges (Report No. RRA2875-1). RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2875-1.html

U.S. Air Force. (2025, February 11). U.S. military space tracking systems strain under new threats. Air Force Tech Connect. https://airforcetechconnect.org/news/us-military-space-tracking-systems-strain-under-new-threats

Wall, C., & Morcos, P. (2021, June 11). Invisible and vital: Undersea cables and transatlantic security. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). https://www.csis.org/analysis/invisible-and-vital-undersea-cables-and-transatlantic-security

What do you think? Share your thoughts and join in the discussion around data centricity and literacy in GEOINT at the 22nd annual DGI conference in London from Feb 23-25, 2026.