The Right Tool for the Job: Using Commercial Space for National Security Missions

As someone who has spent nearly a decade interfacing with commercial providers in space, I’ve witnessed exciting developments such as proliferated small satellite imaging constellations and challenges such as integration of broad-area data into existing tools and workflows. A key challenge in the national security geospatial domain is the transition from a national space paradigm to a national-plus-commercial space paradigm to realize New Space effectivities that will increase decision advantage. Strategies and speeches from government space leaders proclaim a desired level of collaboration and integration while the risk tolerance and incentive structures at the working level continue to block any meaningful change. At this moment, there are no sustainable solutions. Will the government unlock the potential of the private space industry or continue to lose pace?

What is Commercial? The term “commercial” is widely overused and poorly understood in conversations about the space domain. When the government states a strategic imperative to use more “commercial” solutions, they often mean a combination of attributes that are desirable because they are routinely unavailable in traditional government development and acquisition programs. Such desirable commercial attributes include:

- Reduced capital start-up costs because of private investment

- Reduced capital costs from the reuse of COTS components (both HW and SW)

- Reduced lifecycle costs from dual-use capabilities enabling commercial revenue

- Increased speed to market because of industry’s best practices; this includes faster technical learning and a greater ability to recruit and hire new talent

- Increased speed to market because of higher risk tolerance; this encompasses the bias for product iteration vs. requirements/design perfection and zero-risk development common in the government

- Increased speed to market from uninterrupted development flow; this includes being uncoupled from government requirements development cycles, government budget planning cycles, poorly managed government acquisition programs, and burdensome regulations

What are National Security Missions? Often termed “Defense & Intelligence” (or “D&I”) missions, these include monitoring foreign military facilities/movements, characterizing foreign military capabilities, and searching for new military facilities. Advanced warning of economic security risks from natural disasters, market uncertainties, civil unrest, and resource competition are also more relevant to national security than ever before.

The Challenge. Most D&I users in the U.S. space community have been conditioned to using only classified data sources on classified networks. Their most advanced tools and workflows exist on these unreachable networks, and it is an unnatural act for these users to operate at an unclassified level with companies who operate in an open environment and Internet services. Even government acquisition efforts that claim a desire for non-traditional, small business, and/or commercial participants are often artificially closed to those very actors using classified requirements and restricted system access. Even without any actual legal or security restrictions, these deep-rooted architectural, cultural, and human factors barriers are significant; often representing an impossible path to success. Change to allow new commercial entrants a fair hand requires a new paradigm of risk tolerance versus risk avoidance across our security, acquisition, and management professionals without any incentive structure in place to enable it.

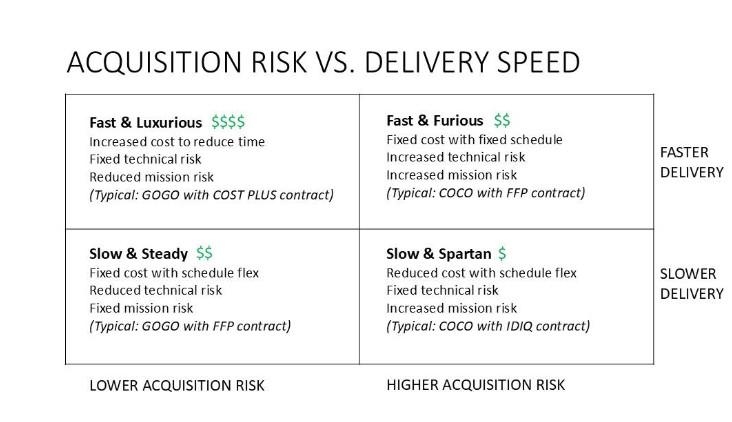

Time vs. Risk Spectrum. Tactical military commanders naturally understand the time vs. risk spectrum in their activities. This same decision-making calculus now needs to be instilled in the space acquisition professional. Accepting acquisition risks to generate the potential for better mission outcomes must be rewarded instead of disincentivized. Too often an acquisition professional is rewarded for simply spending their budget on a program that fails to deliver capabilities. This unfortunate mismatch in the acquisition professional incentive structure disregards the opportunity cost of NOT choosing a commercial solution because this analysis is completely opaque to the system. That opportunity cost may include increased costs, delayed schedules, and less mission capability. The graphic below highlights differences in delivery speed versus acquisition risk and identifies a typical acquisition strategy in each category. Most U.S. space acquisition programs fall on the left side of this diagram while notably the Space Development Agency (SDA) opted for “Fast & Furious” acquisitions to break the cycle.

Graphic depiction of various acquisition approaches

GOGO = Government-owned; Government-operated

COCO = Commercially-owned; Commercially-operated

FFP = Firm Fixed Price

IDIQ = Indefinite Delivery; Indefinite Quantity

The Way Forward. Looking ahead, I see the future of commercial space as driving new technology advancements faster than government space programs. A potential solution to “nudge” government space acquisition decision-making in the direction of embracing more commercial space capabilities in their programs would be a requirement to show the utility/speed vs. risk calculus during any alternatives analysis or similar decision forums prior to finalizing a solution + acquisition approach. Current program managers in the U.S. are often taught to manage across three opposing factors in the performance of their programs: cost, schedule, and performance. We should add “risk” as a fourth factor that must be balanced against the other three. There is mission risk accepted when delaying schedule or reducing performance. Program managers must have a means to articulate how selecting different acquisition strategies and solution providers (e.g., GOGO vs. COCO) may improve their program schedule (and perhaps also cost and performance) by accepting greater risk when choosing a commercial solution over a government one. I believe that forcing a new doctrinal calculus along with a modified incentive structure can finally create the alignment between commercial and national space acquisition needed in an era of global competition.

About the Author:

David Gauthier brings nearly three decades of experience in U.S. national security as a military intelligence officer, technology innovator, and IC senior leader. As Chief Strategy Officer for GXO, Inc., he helps private space industry innovators improve security-related services. Mr. Gauthier is also a Senior Associate with the Center for Strategic Intelligence Studies (CSIS) and a Fellow with the National Security Institute at George Mason University.